On November 13th, 2024, Dr. Dilşa Deniz came to present on the Kurdish mythological figure, Shamaran. Shamaran, who is the Mother goddess in traditional Kurdish religion and in Alevism, is depicted as half woman and half snake. Dr. Deniz discussed how Shamaran is part of almost every Kurdish home, often on dishes or decorations. Her story is quite sad at first, however, Dr. Deniz argued that the story is really symbolic of the process of motherhood, as representative of the Mother goddess. Dr. Deniz expressed the need for more scholarship on Kurdish mythology as the field has been largely untouched, ignored, or incorrectly labeled as belonging entirely to another culture.

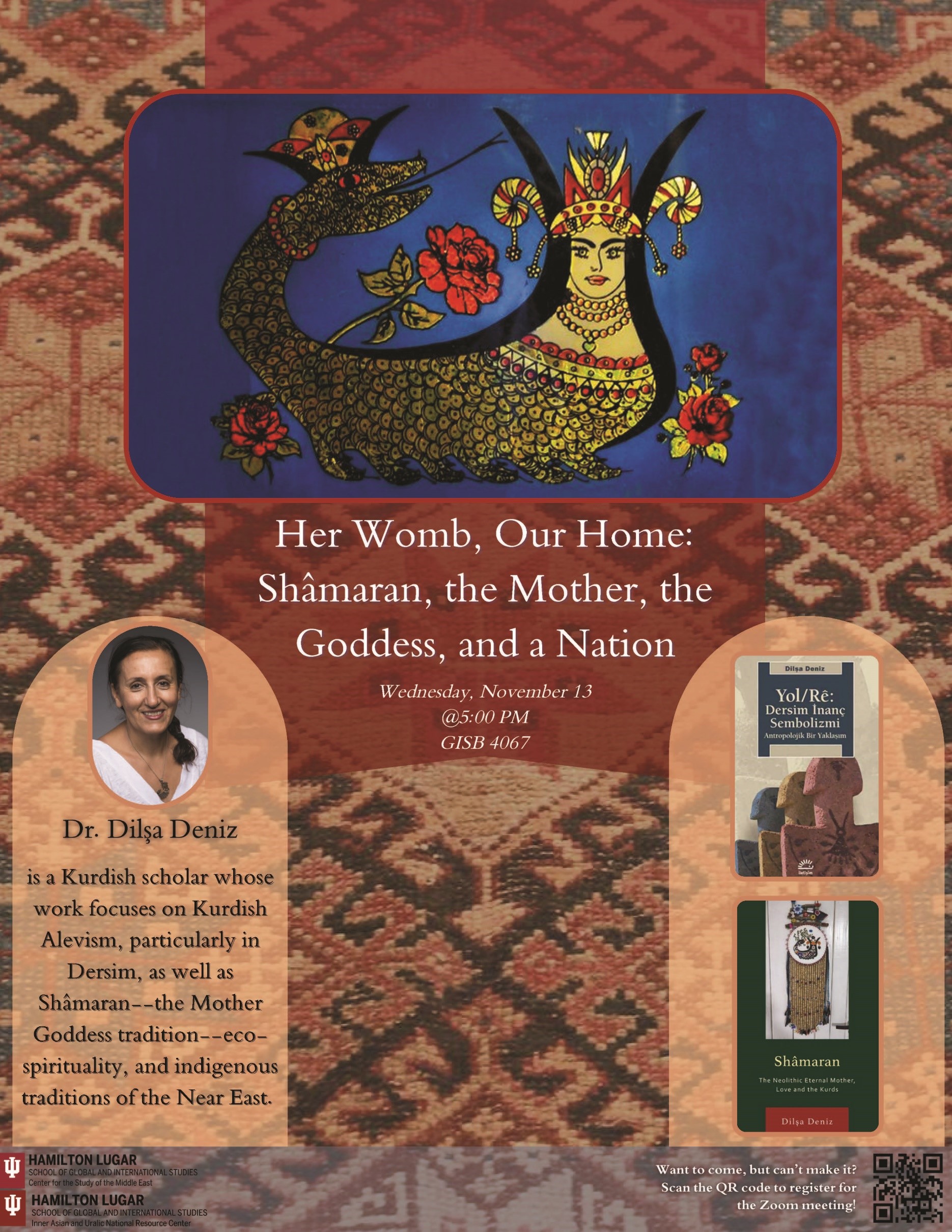

Shamaran is a symbol of traditional feminine beauty. Dr. Deniz pointed out that Shamaran’s look has been changed recently in the modern age, to having a small nose and blue eyes. However, this would not be considered attractive in Kurdish culture. She is usually depicted as having horns, symbolic, Dr. Deniz said, of fertility and the vulva. Shamaran sometimes is also depicted as having insect antennas or bull horns, both signs of fertility. The Mother goddess is usually shown wearing a heart necklace, which is a symbol of her, and having zigzags or dots which the presenter stated are symbolic of the snake goddess of the Neolithic Era. Shamaran has no arms or legs, consistent with the Neolithic snake goddess depiction. She is also traditionally shown with plants, and the colors red and green. Dr. Deniz explained that red is symbolic of regeneration, and green is symbolic of the birth/death cycle.

The legend of Shamaran entails a boy who tries to survive with his mother by getting wood to sell. When he is out with friends one day, a storm comes, and they go to a cave to get protection. He begins to play with a stick and finds a flat stone, underneath of which is a large jar of honey. He and his friends sell this honey, and have to come back to collect more. The boy must go into the jar/well of honey to collect it, and his friends cover the jar/well with the stone to trap him in there. A scorpion comes through a crack in the jar and the boy kills it. The boy goes out of the jar where the scorpion came in, and finds a garden where he sees Shamaran, a beautiful half woman, half snake figure. She promises not to harm him, but says he cannot return to the human world as it would be dangerous if people found out where she was. He becomes very homesick, and Shamaran tells him he can return but that he cannot tell people where she is, or bathe in hamams (public baths), unless it was a life-threatening situation. He leaves and takes his mother with him to a remote place. In some versions of the story, Dr. Deniz said there is a king or his daughter who is sick, and needs the blood of Shamaran to be cured. People are forced to bathe to see if they have the mark of the Shamaran, and eventually the boy is forced to bathe in public, which reveals he knows the place of the Shamaran. They find her and she tells the boy that if they ask him to kill her, to refuse. She is killed by the authorities, but there are 3 different outcomes from her blood: healing, death, or knowledge. The boy gets knowledge from her body, and the king or his daughter gets the poisonous part. However, eventually the king or daughter is healed. In many version, Dr. Deniz said, the boy would marry the daughter of the king, and become king.

Dr. Deniz argued that the cave in the story represented the womb, and the process of the boy going into and through the jar represents the process of seed traveling to the womb. Furthermore, she said the entrance of the cave represents the vulva, and that the scorpion represents, even in Zoroastrian texts, something that kills human seed. The boy kills the scorpion and is able to “sprout”, where upon the Mother goddess decides how long he stayed until he is able to go to the human realm. This, Dr. Deniz explained, represents the life and death cycle, and the reincarnation system. In traditional Kurdish religion, she said, life and death were a balance and held duality. This was not a good/bad duality like in Abrahamic religions, but rather a focus on the duality of life and death. For example, she showed Shanidar Cave, where ritual burial was practiced by the Kurds, and flowers were put there in honor of rebirth. The shape of graves was round to symbolize pregnancy, but in this case, a symbol of that person returning. She argued that monotheistic religions took this same symbolism as their own, but instead constructed Satan in order to demonize the mother goddess. Likewise, in Kermanshah, there is the Temple of Anahita, which features a dome to represent the fertility goddess Anahita. Dr. Deniz argued that this archeological feature was also appropriated by Abrahamic religions. She underscored another important site for the mother goddess, Gire Mirazan, which is 12000 years old and a temple for the mother goddess. The site had a round shape and t shapes with pillars. In Alevism, Dr. Deniz explained, black is the most important color as it is the symbol of the mother goddess, and a symbol of protection.

Dr. Deniz also argued that there is a misunderstanding around the name of Shamaran. It is traditionally understood as coming from “xšaya/xšaθra”, from Avestan, translated as “king” or “lord”. However, she noted that Mary Boyce, a famed scholar of Zoroastrianism, said that xšaθra is related to the mother goddess, Armaiti. The presenter said that Zoroaster diminished Armaiti’s role. Thus, she said there needs to be an attempt to not have the “sha” part of the name reflect a masculine role. “Mar” is the Kurdish word for snake. Dr. Deniz concluded by saying that Alevism has become disconnected to its past. Even Muslim Kurds have Shamaran in their homes, making her a cross-religious figure. However, many people do not know the importance of the mother goddess in the region or the way in which their ancestors revered her. Dr. Deniz explained how the Shamaran is a key symbol of the Kurdish people.