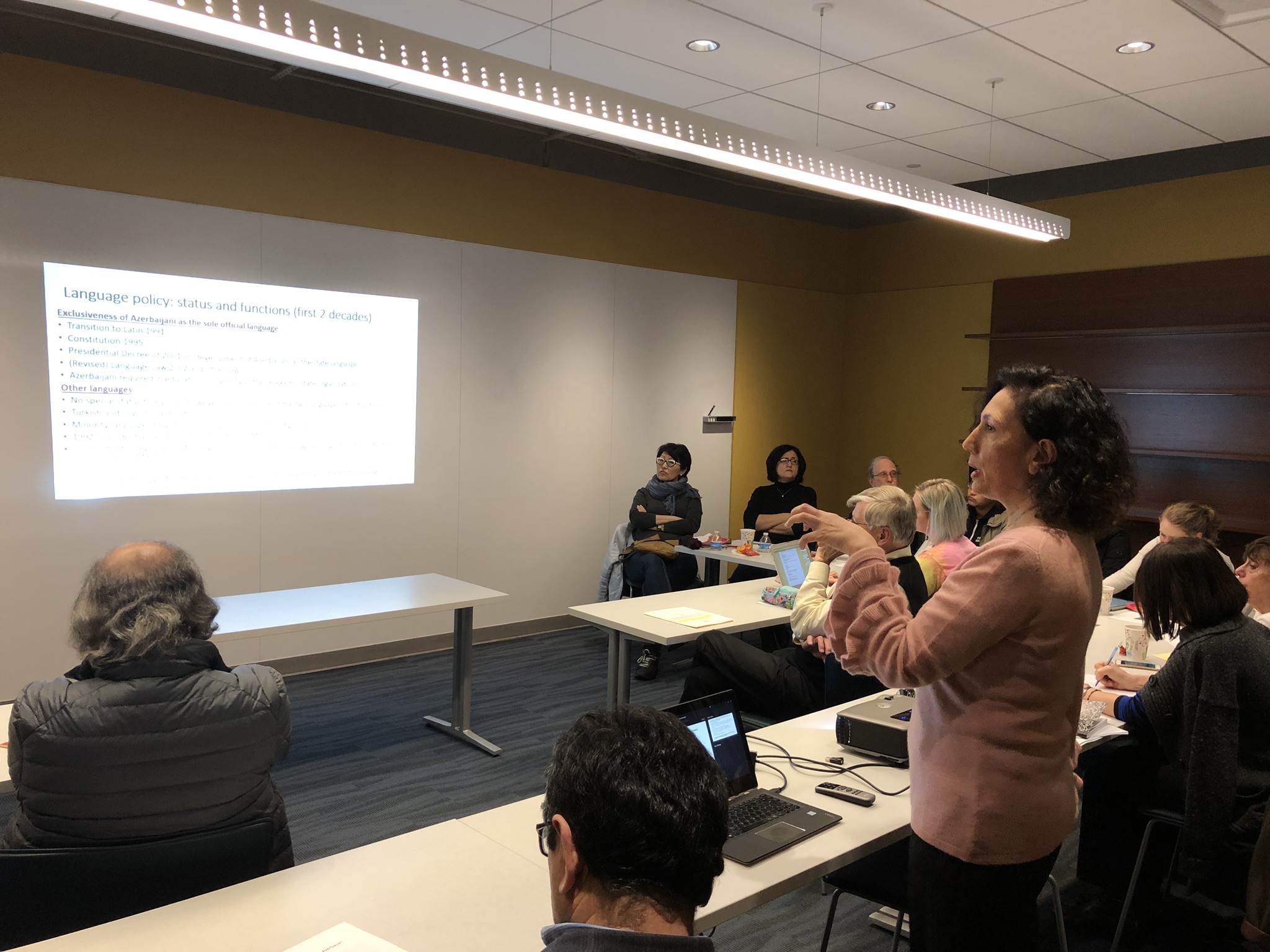

Dr. Jala Garibova was a Fulbright Scholar at Indiana University, where she pursued her research project in sociolinguistics. Her areas of interest are language and identity relationships and language policy issues in Azerbaijan and the post-Soviet Turkic Republics. Dr. Garibova teaches sociolinguistics at Azerbaijan University of Languages. She is developing a textbook on sociolinguistics for Azerbaijani students as her Fulbright project.

Her published work includes articles, book chapters, and books on language policy and linguistic attitudes in Azerbaijan and the other post-Soviet Turkic republics, language legislation in the Republic of Azerbaijan, and language and identity relationships in the post-Soviet era.

Introduction

Azerbaijan, one of the six Muslim and five Turkic-speaking sovereign republics of the Soviet Union, gained independence in 1991. As for all Soviet republics, to one or another degree, independence was partly (and implicitly) initiated by processes that were already underway in late 1980’s, especially through the implementation of the policies of glasnost and perestroika.

A close review of nearly three decades of Azerbaijan’s post-independence development shows three main strategies of identity reconstruction: policy formulation and legislation, construction of symbolic and discursive resources, and social engagement. These strategies, in turn, have produced three different modes of expressing identity within society, which I regard, respectively, as adaptive, perceptive, and agentive. The first two strategies were more characteristic of the first two decades after independence, while the third one gained more salience during the third decade of independence. I therefore consider the identity construction strategies of the third decade separately from the policies of 1991-2010.

De-Sovietization: Discourse, Symbolism, and Action (1991-2010)

If I try to formulate what the major ideology of post-independent nation-building in Azerbaijan was, I would specify it as “Azerbaijanism.” If I try to formulate the major features of implementing this ideology were, I should probably highlight the tendency of de-Sovietization. De-Sovietization occurred across the entire post-Soviet space with varying degrees of intensity, depth, and breadth in each emerging state. De-Sovietization was an all-embracing process and a key marker of independence. It defined the route for the reconstruction of identities and was intended to promote integration at the national and societal levels. Along the way, de-Sovietization produced its own sub-processes, which could certainly be seen as separate developments. However, because these tendencies emerged in conceptual opposition to what the Soviets outlined as markers of sovereignty for the member republics, we tend to look at them as sub-processes of de-Sovietization. In the context of Azerbaijan, I regard the following as the major sub-processes: a) revival of nationhood, b) establishing roots, c) global integration, d) modernization. All these sub-processes had varying degrees of intensity depending on the period after independence and the visions of the ruling elites at that time.

Revival of Nationhood

Most prominently, revival of nationhood took the form of re-writing national history, reconstruction of narrative and symbolism, revisiting the connection with religion and faith, stronger emphasis on traditional art and music genres, and language and education policy. Except for the name of the titular nation and the language, all other symbols of Soviet times were replaced. The flag, the state emblem and the national anthem designed and composed during the Azerbaijan Democratic Republic (1918-1920) were brought back as symbols of the new independent Azerbaijan.

Historical narratives placed a strong emphasis on the statehood traditions of Azerbaijan since very old times. Heroes forbidden during by the Soviets were revived in historical and literary narratives and media presentations. The early period of independence coincided with the loss of territories on the side of Azerbaijan due to the conflict with Armenia over Nagorno-Karabakh; hence, the reconstructed historical narrative emphasized how the Soviet regime drew up artificial borders to keep territories under control and prone to ethnic conflict.

The construction of new heroes (or the reconstruction of old ones) was most visible in the framework of city planning, i.e., replacement of onomastics (street names, city names, district names) and statues. Street names were changed to honor famous Azerbaijanis forgotten or forbidden during Soviet times. Statues dedicated to Soviet heroes (including Azerbaijanis who were supporters or promoters of Soviet power and socialism) were demolished and replaced with statues to new heroes — mainly those from epic stories, or literary and artistic figures. This can be seen as an extension of the Soviet nation-building policy: in promoting folkloristic heroes and creators of literature and art, the early independence policy was to some extent resonating the Soviet way of ideology enhancement through folklore, literature, and art.

Traditional national holidays such as Novruz, the celebration of which was discouraged (if not forbidden) during Soviet times were revived and became one of the new national symbols. Celebrations of Novruz also included and thus revived traditional sports and dances, which can be viewed as construction of identity through collective action. Traditional art and music genres, such as Mugham, miniature art, and carpet-weaving, have been promoted at the state level.

Although criticism of the restrictions on religious freedom by the Soviets was part of the anti-Soviet discourse, Azerbaijan declared loyalty to the secular way of life, placing Islam on the cultural stratum of the identity construction.

Azerbaijani has had the status of a state language since 1956, thus enjoying de facto official usage for a long time before independence. Therefore, institutionalizing the post-independence official status of Azerbaijani was not as painful as it was in other parts of Central Asia. Alongside preparing the legislative basis for the official status of Azerbaijani, an active discourse emerged around the importance of Azerbaijani as a mother tongue. The most important step taken in this direction was the shift to the Latin alphabet in 1991. Vocabulary intervention was also intensive, especially, in the first years of independence through the replacement of foreign words with those with Turkic roots.

Establishing Roots

Two different generations of political power promoted different strategies in regard to the search for historical roots. Promotion of the Turkic roots of Azerbaijaniness (a topic discouraged/forbidden under the Soviets) to the larger public was prominent both during the Popular Front era (1991-1993) and the present political era (1993-to present). But there was a slight difference in the focus of the discourses in these two eras.

The Turkification tendencies were a kind of response to the trauma of Soviet times. This tendency was most remarkable during the period when the Popular Front was in power. This group was mainly represented by middle class intellectuals most of whom were dissidents during the Soviet times, few from Baku, and for many of whom Russian was the second or even the third language. In the context of Soviet realities, these people did not occupy a place as high in the social hierarchy as Russian-speaking elites from Baku did. They therefore were explicitly and acutely opposed to the use or promotion of Russian in any possible function while embracing the ideology of Turkicness and use of Turkish instead. Although the ideology of Azerbaijaniness was important for them, this ideology was experienced and promoted in the context of Turkicness as a corporate identity.

With the change in political power after 1993, the emphasis was shifted to creating discrete Azerbaijani symbols, certain aspects of which (for example, the name of the language) were legalized with the adoption of the new constitution. The new political elites, with the rich experience of ruling from Soviet times, came from a different socio-cultural environment where Russian language and culture were dominant and significant as a marker of social prestige. They did not have the same sensitivity toward affiliation with the greater Turkic world, which was more peculiar for marginalized groups. Their prestigious social position during the Soviet times had made them comfortable with being Azerbaijani without thinking in terms of a broader identity. At the same time, they were more tolerant towards the Russian element and some shared Soviet values (especially in culture). De-Russification therefore started to slow down (especially in political discourse) after 1993. This, however, did not preclude discourse on the Turkic roots of Azerbaijanis: Turkicness was an important building element in the construction of historic awareness of ethnic roots. Nevertheless, it was not decisive (but was still important) for the construction of the national or social identity of modern Azerbaijan. The motto “One nation, two states” describing the relations between Azerbaijan and Turkey is an evident illustration of this.

The official language policy was persistent in demanding the exclusiveness of Azerbaijani as the sole state and official language. It was reflected in all legislative acts and official documents. This certainly changed linguistic attitudes and behavior patterns. New monolingual and bilingual patterns were emerging. Although the discourse surrounding Russian had become more tolerant and even goodwill-based, language practices were following the official language policy rather than language discourse.

Global Integration

Since the first years of independence, many Azerbaijanis have viewed Turkey as the most reliable partner in and for Azerbaijan’s integration in the international community. Particularly in the early years of independence, Turkey’s role in identity construction (both national and social) was considered very important from the following perspectives as: a) the culturally and ethnically closest nation — no/minimal linguistic or cross-cultural barrier, b) a Western-style Muslim country, which can be looked upon as a model for modern, secular state-building in an Islamic context, c) an example of the harmonious integration of Islamic traditions which does not violate secular principles of statehood and can be looked up as a model for bridging secularity with tradition, d) a reputable country in the modern capitalist world — a gateway for international political and economic integration.

New Dimensions of Identity Reconstruction: Policy and Discourse (post-2010)

The key factors of identity construction are still active with slight variance in intensity or focus. The last decade is characterized by a shift of the discursive focus from de-Sovietization to the independent development of Azerbaijan and Azerbaijani national pride. De-Sovietization nevertheless is still an important tenet behind the philosophy and format of any new action, such as reforms, restructuring, recruitment policies, etc., which is taken towards enhancing modernity and development. The initiative to recruit younger, more progressive cohorts is growing, but the process will probably take some time. There exist implementation problems mainly due to the lack of experience in human resources management and to the still significant number of decision-makers not fully embracing the change.

The search for historic roots has been built into the discourse, policy, and symbolism of the nation-building/nation-development. Although reference to the ethnohistorical traditions in the form of promoting the Turkic origins of Azerbaijaniness is still significant, contemporary discourse also draws attention to the construction of roots in the context of historical geopolitical realities such as through references to the place of Azerbaijan along the Silk Road.

Construction of National Pride

Reverence to national symbols as well as to the cultural heritage of Azerbaijan is a continuing trend; contemporary public figures receive substantial attention. Personalities representing the cultural heritage of Azerbaijan have been gaining more prominence. This year of 2019, for example, has been declared the year of Nasimi in Azerbaijan.

The history of the Azerbaijan Democratic Republic (1918-1920) has gained considerable attention in recent years. This new level of attention coincided with the hundredth anniversary of the establishment of the Azerbaijan Democratic Republic and produced a strong positive response from society. The government sponsored the publication of the works and biographies of the founding fathers and the collections of media they created and published during their lifetimes. There is also some criticism, through media and social media discourse, of the previous years when these personalities did not receive due attention.

Multiculturalism was declared Azerbaijan’s state strategy in 2013. It is also promoted as a source of national pride and therefore should be seen as an identity-shaping factor. This strategy has also generated discourse on tolerance and cross-cultural dimensions of Azerbaijani society, enabling harmonious co-existence of different cultures, languages, and religions. Azerbaijan is considered one of the most tolerant and welcoming societies in the world, and this has received attention in multiple international media resources. There is growing support to publish textbooks and language resources in minority languages; however, more needs to be done in terms of implementation and resource allocation.

The state also shows due respect to religious traditions and holidays, such as Ramazan and Gurban, but they are reconstructed mostly as part of the cultural heritage, and secularity is the core accompanying topic of any discourse or policy surrounding religion. At the same time, religious activities provoking racial or national hostility and radicalism are strongly discouraged and legally prohibited. Religious tolerance and respect for other faiths is promoted as distinguishing features of the Azerbaijani nation.

Increased access to religion has certainly brought visible changes in the society, such as more people celebrating religious holidays or practicing Islam. Although religious outfits such as hijab did not gain high popularity, other religious practices such as fasting, practicing Namaz, and abstaining from alcohol are encountered more frequently in comparison with Soviet times, especially among younger generations, including Russian-speaking groups.

Although more acute (but implicit) during the early Soviet times, the perceptions of a Sunni-Shiite divide do not affect perceptions of identity. This division has not been politicized or officially encouraged. There is, however, debate over the historical role of Shiism (viewed mostly negative by Turkists) in alienating Azerbaijani Turks from Ottomans. From this perspective, even though Shah Ismail Khatai has been elevated to the status of Azerbaijan’s national hero and the founder of the Safavi State in official discourse, his historic role is not so much acclaimed by certain Turkic-oriented circles.

International Integration

National interests are the focus of international policy, which was also articulated in one of the most recent interviews that Ilham Aliyev, the President of Azerbaijan, gave to local television media in Azerbaijan.

Turkey continues to be prioritized in international relations. Azerbaijan’s response is reciprocal: for example, immediate action was taken to close the network of Gulen schools in the country. There is, however, a slight decline in the popular perception of Turkey as a gateway for Azerbaijan to international integration or a model for a modern statehood.

A more tolerant official position has been taken towards Russia and Russian recently. Although emphasizing the independence of Azerbaijan, official policy has interpreted positive relations with Russia in the context of the necessity to strengthen local policy and regional cooperation. The Russian language has come to take on the role of a soft power resource in strengthening Azerbaijan’s position in regional cooperation. Concrete steps have been taken to implement the intensive study of Russian in certain secondary schools. Additionally, Russian has recently been reappearing as part of job requirements for many commercial organizations and businesses.

Constructing Agentive Identity

With the progress of nation-building, top-down identity policies themselves produce and encourage social engagement by enabling social agency. Social agency includes active involvement and contribution of an experience into the overall ideology. Social agency can react in the form of mirroring the top-down ideology and patterns of its expression. But it can also be creative and produce its own (sometimes opposing and sometimes simply alternative) patterns of loyalty to the ideology, especially with regard to the national one, which is usually regarded as indisputable for all social groups. The discourse has recently been focusing on social agency and action as an expression of national spirit and patriotism. And concrete steps have been taken to engage the youth as active participants in patriotism. Recent political discourse has also been emphasizing the importance of constructive patriotism for modern nation-building.

Azerbaijan has recently been hosting popular global events such as the Eurovision song contest, European and Islamic Olympic Games, and Formula 1 competitions. In popular parlance, these are mostly interpreted as important steps to make Azerbaijan known to the world, and to attract tourism as well as to enhance the international image of the country. High-level public events appear to play an important role in strengthening optimism and pride among the youth in regard to the image of Azerbaijan. Most of them express this also through active participation in the organization of these events. All this does not certainly go without criticism from certain groups in society.

The state program on sponsoring education abroad has produced a rich resource of young specialists. The government organizations are encouraged to recruit from among these young experts which contributes to the positive profile of the government and helps the state to engage these people as contributors to modern state-building.

Culture is seen as an important component of identity construction. It is also viewed as a continuing symbol of modernity and secularity. But it also has an ideological challenge: culture is seen, perceived, and communicated as a marker of social prestige, which is also utilized as a tool for social integration. Through the combination of the traditional and the global in art production, the eclecticism of Azerbaijani society is communicated in perceptions of uniqueness. The narrative and event promotion focus on the most prominent features of Azerbaijani cultural tradition (classical music, jazz, mugham, dance, etc.) for the construction of perceptive and agentive identity. Not only recognition but also engagement is promoted as an articulation of identity, and growing numbers of young people have been involving themselves in art production.

Language Attitudes and Practices

The very fact that Azerbaijani became the official language required a solid knowledge of the language in state-owned enterprises, many international and local business, as well as for admission to universities. This elevation in the status of Azerbaijani caused an accompanying decline in the knowledge of Russian. It is not unusual in Baku to encounter monolingual young Azerbaijanis from bilingual families as well as Russian-Azerbaijani bilingual young people whose parents do not speak Azerbaijani. Neither of these patterns was possible during Soviet times, especially in Baku. This has created a vast array of opportunities for the Azerbaijani-speaking segments of the population, including Azerbaijani monolinguals in certain cases, to participate in the political and social life of the country. These groups were deprived of such participation during Soviet times. With the increase of the role of Azerbaijani, Russian monolinguals have gradually been losing their place in political and social life. Thus, the rise of the new Azerbaijani-language elite caused decline in the political prestige of the Russian-language elites (mainly Russian monolinguals) leaving however the niche of socio-cultural prestige intact. Russian, however, is still present and has recently gained a higher degree of utility in particular in the commercial and service sectors. Although lack of competence in Russian is not an explicit barrier, it can still implicitly deprive youth of solid job opportunities in a considerable portion of the private sector.

Sociolinguistics surveys show that, contrary to possible expectations, the attitude towards Russian among the youth is rather positive than negative. Russian is still seen as a language of cultural prestige and exposure as well as the one providing better job opportunities in the commercial sector.

Many Azerbaijanis respect Turkish and regard it as an important language that enables access to international resources (especially for those who are not active users of Russian or English) and international education. Also, as the quality of Azerbaijani schools was not satisfactory during the first two decades of independence, people saw Turkish schools as a natural replacement for Azerbaijani ones. However, according to opinion surveys, people express caution in terms of potential influence from Turkish on Azerbaijani. There is a strong resistance in academic circles to casually borrowing Turkish words.

A sociolinguistic survey of the situation of minorities in Azerbaijan shows stable diglossia rather than an overall shift. Minority languages are not languages of instruction, however; they are taught as local languages during four years (and in the case of a few languages, during nine or 11 years) of secondary school. Minorities use the native language at home and within the community. The knowledge of Azerbaijani is solid and functional. This is not the case, however, before the school age in regard to many communities (especially to most isolated ones). School officials report that due to the lack of the knowledge of Azerbaijani among children in the early years of schooling, teachers often switch to local languages, thus unofficially implementing bilingual education. Minorities take pride in their native language and culture and language transmission is still active. However, migration tendencies, tourism, and the newly realized (among the rural population) potential of English could potentially have a negative effect on language maintenance.

Articulation of Identity: Who Am I?

Although the feeling of Azerbaijaniness is strong and supported by state ideology, some people still reject the term “Azerbaijani” and blame the 1938-1939 Stalinist decrees for changing the name of the nation (Türk) to a geographically-based term (Azerbaijani). Interestingly, awareness has been growing with discourse on ethnic minorities stemming from the declared multiculturalism policy. Minorities articulate a two-fold identity — ethnic and national. They say, for example, “I am Tat by my ethnic origin, but I am also Azerbaijani because Azerbaijan is my motherland. It is obvious that to them ethnic identity is separate from citizenship. This is not the case with many Azerbaijanis. It is interesting to see how this two-fold identity articulation on the side of minorities has affected the perception of Azerbaijaniness among representatives of the titular nation. Some people are discovering the fact that they had never known or thought about what the name Azerbaijani means. And now with the indigenous groups’ articulation of Azerbaijaniness as the corporate-national, supra-ethnic identity (which communicates to them that the term Azerbaijani is a supra-ethnic label), they start to question their own ethnic belonging by asking themselves: “Who am I?” This certainly encourages further reflections about Azerbaijani versus Turk as ethnonyms.