This semester, I embarked on what everyone told me was an ambitious project, but I simply thought sounded like good, clean fun. I decided that I would learn Kyrgyz in an hour a week. Every year the IAUNRC’s affiliate department, Central Eurasian Studies (CEUS), hosts a number of Fulbright Language Teaching Assistants from the various regions that we cover. This year, we have native speakers of Kazakh, Kyrgyz, Mongolian, Pashto, Turkish, and Uzbek. When CEUS language coordinator Piibi-Kai Kivik sent out an email reminding us that we had a Kyrgyz instructor with no students, I contacted her about arranging something. Unfortunately, I was preparing for qualifying exams and working full-time, so I was unable to arrange anything official, but I started meeting Azamat, our Kyrgyz FLTA, for conversation hours in an attempt to learn the language. While this may sound ambitious, given my background in Turkic languages (Uyghur, Turkish, and Chaghatay) it actually seemed quite feasible to me.

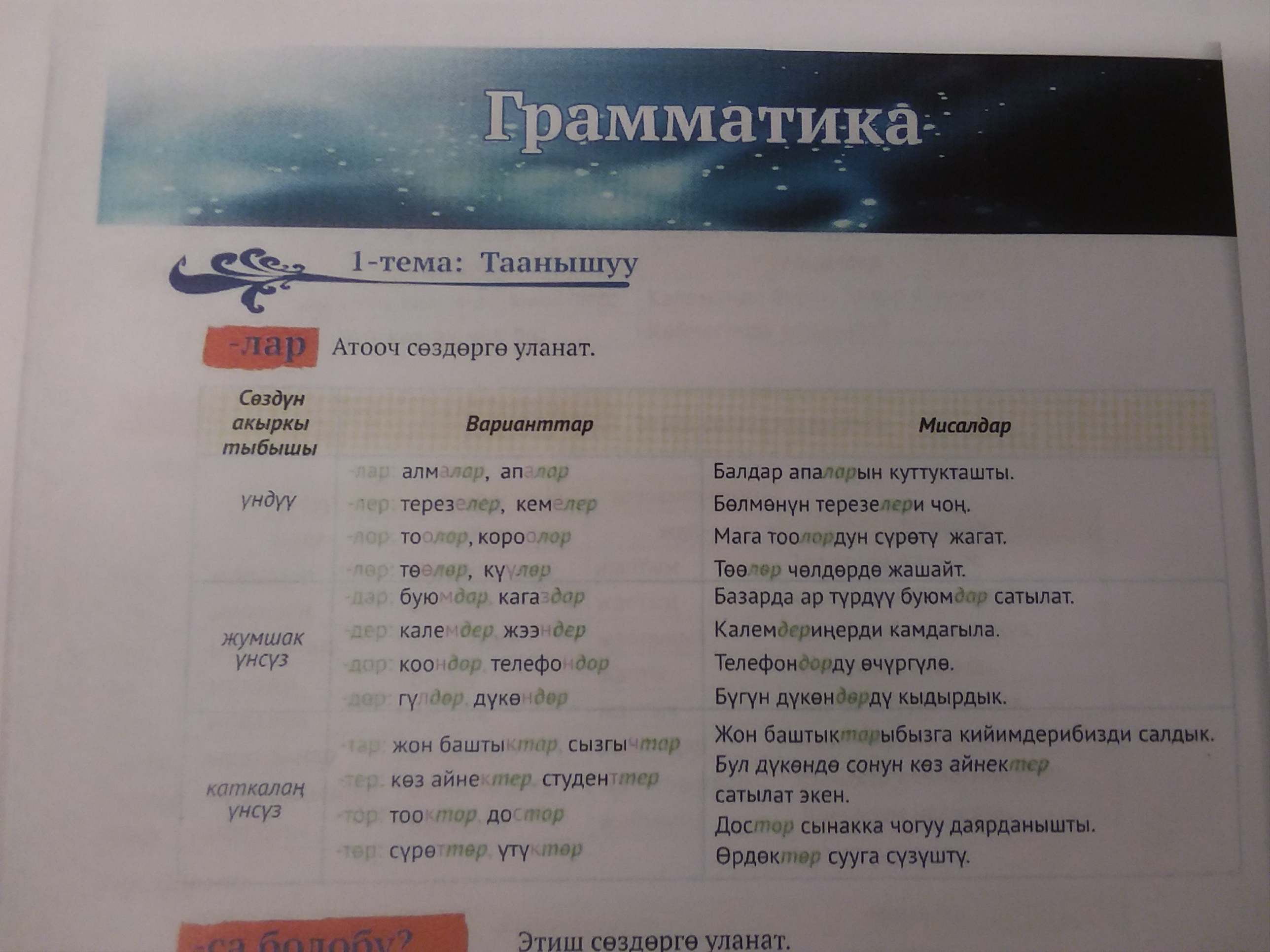

We began by going through some Peace Corps material that was basically just set phrases—‘hi, how are you?’ ‘I’m well, thanks,’ and the like—and eventually got into more serious grammars. Since there is not really a textbook available for native English-speakers to learn the language, we had to make do with the materials we had. I found that the easiest way for me to dig into Kyrgyz, was simply to ask Azamat questions about how Kyrgyz differs from the Turkic languages I know.

A brief aside here to explain Turkic languages. Turkic is a language family that consists of (among other, less common languages) not only Kyrgyz, but Uyghur, Uzbek, Kazakh, Turkmen, Turkish, and Azerbaijani. They are all fairly identical in structure and, barring certain phonetic changes, much vocabulary, as well. Where they tend to differ is in the structure of verbs. That is not to say that they are terribly different, but endings tend to differ between them. Vowel harmony, too, can change slightly.

In any case, I was fairly certain that I could learn Kyrgyz by learning the grammar and some vocabulary and then speaking it for an hour a week. So we set out to see if it was possible. As it turns out, it is one hundred percent doable—I just didn’t do a very good job of it. I’m not sure you could call what I speak exactly “Kyrgyz,” even if it is discernably Turkic and able to have a conversation with a native speaker who dumbs his speech down a little bit. I’m not fully convinced that the noises coming out of my mouth when I try to speak Kyrgyz are much more than something I would describe as “heavily-accented Uyghur with minor Anatolian elements and a few verb endings that I’ve worked out are distinctly Kyrgyz.” Azamat, though, reassures me that I’ve made pretty good progress for only thinking about the language for an hour a week.

Regardless, it was certainly an interesting experience and it’s heartening to know that it’s possible to pick up the rudiments of a language in such a fashion.