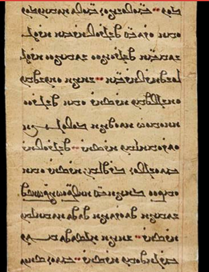

On April 24th, 2025, Prof. Gábor Kósa came to the Department of Central Eurasian Studies and the Inner Asian and Uralic National Resource Center to speak on the scholarly debate on the similarities between some recently found Chinese Manichaean documents, and the Uyghur Xuāstvānīft. As part of his overview of Manichaeism, he explained that there is a large corpus of Manichaean texts from Egypt, Central Asia, and China, but almost none from present-day Iraq and Iran, the origin places of Manichaeism. He also introduced some Manichaean confessional texts from Turfan, which the Uyghur Xuāstvānīft is part of. These types of text, Prof. Kósa explained, detail how the “hearers” (Manichaean lay people) and “elect” (the elites of Manichaeism) should confess their sins. He also noted the discovery in the past 15 years of a dozen Chinese Manichaean paintings that are now kept in Japanese collections, for the most part. The corpus of Manichaean texts that Prof. Kósa focused on were from the city of Fuqing, Fujian province in Southeast China. These texts were first mentioned by Li Linzhou in 2017. Prof. Kósa said that the discovery of Fujianese texts was not a complete surprise, as the 16th century Minshu mentions a 9th century Manichaean teacher fleeing to Fujian. Prof. Kósa explained that the Chinese scholars Yu Lunlun, Cao Ling, and Zhang Fan have noted the similarity between Fujianese confessional manuscripts and the Uyghur Xuāstvānīft. Prof. Kósa underscored that all manuscripts of the Uyghur Xuāstvānīft, except for one, are missing the beginning. The word xuāstvānīft, the speaker explained, is from the Parthian language (wxāstwānīft), from which it was loaned into Sogdian and then into Uyghur. Furthermore, Prof. Kósa said some Parthian phrases are included in both the Sogdian and Uyghur Xuāstvānīft, which may point to the Parthian original, of which, however, we have nothing left. Prof. Kósa gave evidence that the Fujianese confessional texts have similar words usage to the Dunhuang Hymnscoll, which was a translation of a Parthian original. He then explained many differences and similarities between the Uyghur Xuāstvānīft and the new Fujianese confessional texts, concluding that while the structure and message are basically the same, the wording is quite different. By providing some specific pieces of evidence, in total, he said, the Fujian corpus is likely not a direct translation of the Uyghur Xuāstvānīft, but rather, he argued, a translation from a Parthian original text. Prof. Kósa said that if his argument is true, then the original of these Fujian confessional manuscripts may ultimately represent the earliest version of the Xuāstvānīft.