This past semester was a busy one at the IAUNRC. In addition to all of our normal activities, like videoconferencing, in-person outreach, and arranging for guest lecturers on campus, we are reapplying for our Title VI grant. Between business as usual and the added headache of writing the grant proposal, no one around here has had terribly much leisure time. Despite all of the craziness slowly encroaching upon the office, I did manage to find the time to undertake a small project of my own: recreating Tamerlane Chess. At the time of writing, I plan to donate the set and a rulebook to the IAUNRC for use by a larger audience.

For those who are not aware, the game that we call chess now developed from a game once played across the broader Persianate world called Shaṭranj, but it was but one of many versions. From what I’m given to understand, chess variants still enjoy a good deal of popularity among aficionados and one of them, that is still occasionally played today, enjoyed popularity in the court of Timur. Timur, better known in the west as Tamerlane, was a Central Asian conqueror who cut out a large empire in the region with its capital at Samarqand and, apparently, quite enjoyed many versions of chess. So great, in fact, was Timur’s love of the game, that a figure carrying the nisbah al-Shaṭranjī (which might be translated “the chess-ist”) held a fairly prominent place in his court. Timur, apparently, particularly enjoyed playing a variant called shaṭranj al-kabīr—or ‘great chess’—which is often referred to today as Tamerlane chess.

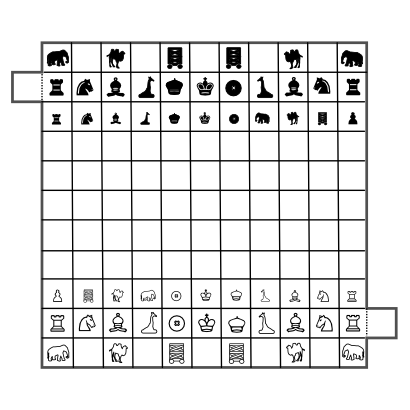

The variant is played on a rather unique board and has rules far more complex than those for modern chess, as well as a number of additional pieces that move in fairly strange ways. In addition to the king, knight, rook, and bishop that are familiar from modern chess, there are such pieces as the general, vizir, elephant, and camel. These pieces move in ways that are somewhat counterintuitive to people familiar with the modern game. The elephant, for instance, moves exactly two squares diagonally and jumps pieces in the way; the giraffe moves one space diagonally and then at least three spaces horizontally or vertically. The pawns, too, are different from what one might expect. Each pawn has an associated major piece and, when that pawn is promoted (reaches the last row of the board and can no longer move), it becomes that particular piece. That is to say that there is a pawn of kings, a pawn of vizirs, a pawn of elephants, and so on. This also means that it is possible for each side to have more than one king on the board, which adds a certain strategic element that is not found in ordinary chess.

Naturally, when I heard about a game that enjoyed great popularity in the court of Timur, I had to play it myself. However, it appeared, after some initial checking around and internet hunting, that it was not possible to simply buy a set of Tamerlane chess pieces. It seems that people are, for the most part, rather uninterested in fourteenth-century chess variants these days. Undeterred, I resolved to build my own. Unfortunately, it also seems that people are relatively uninterested in playing chess variants that are played on a larger board, and I was unable to find anything approaching the requisite 10x11 space board with an additional square dangling off the side (see illustration). So, without pieces and board-less, I was left to cobble something together on my own. I ended up cutting up cardboard chess boards and taping identifying symbols on many of the pieces, but I ended up with a playable set for Tamerlane chess.

I have yet to play an entire game on it, as I hear they can last upwards of a hundred and fifty moves, but it will be here in the IAUNRC, along with instructions, for any future chess aficionados who might come by.